Mental organs

Chapter 8 endnote 7, from How Emotions are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain by Lisa Feldman Barrett.

Some context is:

The evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker writes that emotions are like mental organs, analogous to body organs for specialized functions, and that an emotion’s essence is a set of genes. [...] Each emotion supposedly issues from a specialized “organ of computation” designed to solve a specific problem for your hominin ancestors on the African savanna, so your genes have a better chance of replicating themselves into the next generation. Much has been written on the idea of mental organs and evolution;

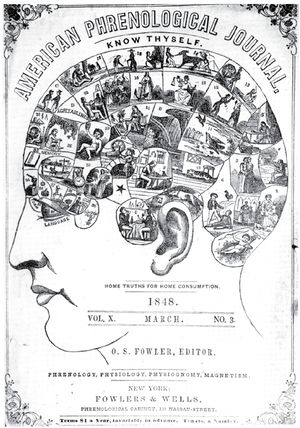

There is a long tradition for mental philosophers and other scholars of the mind to refer to psychological phenomena, like anger, as a "mental organ."[1][2][3][4] This tradition is best associated with faculty psychology, the idea that the human mind is structured as a set of distinct components or abilities, each with its own dedicated process or causal mechanism.[5] The idea of mental organs dates back to the German philosopher Christian von Wolff. The most infamous version of faculty psychology is the neuroanatomist Franz Joseph Gall's phrenology (also called "organology" or "craniology").[6] Gall, for example, wrote “We have to discover the fundamental powers of the mind, for it is only these that can have separate organs in the brain.”[7] In psychology's history, others have explicitly endorsed the mental organ hypothesis,[8] which has been called one of "the great historical contributions to the development of theoretical psychology."[9][10]

Evolutionary psychologists assume that "emotion organs" evolved in hominins during the Pleistocene era, between 2.5 million and about 12,000 years ago. This assumption is consistent with their belief that natural selection works pretty slowly,[11] but contrary to more recent discoveries that natural selection can work pretty quickly.[12]

Just as your heart is built to pump blood throughout the body, and your lungs are built to exchange carbon dioxide for oxygen, each emotion is supposed to have special mechanisms to help you solve the problems of daily living so your genes have a better chance of replicating themselves into the next generation.[13][14][15][16] This includes innate “emotion programs,” such as a jealousy program to prevent cheating on your mate, and a fear program that prevents you from being stalked and ambushed.[17][18]

Most scientists taking a classical view of emotion assume that an emotion organ in the brain is a self-contained, fully detachable part like a heart or a liver (i.e., it corresponds to a localized brain region). But the psychologist Steven Pinker, in his usual fashion, takes a more nuanced approach, suggesting that a metaphorical organ could be wide and sprawling like our blood vessels or the skin. He writes, “It may be broken into regions that are interconnected by fibers that make the regions act as a unit.” That is, an emotion's essence could be a distributed brain network. Pinker also suggests an emotion organ might not be localized to a network, but instead might be more like a brain state: “[it] probably looks more like road kill, sprawling messily over the bulges and crevasses of the brain.”[19]

Notes on the Notes

- ↑ Chomsky, Noam. 1980. “Rules and Representations.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3 (1): 1–15.

- ↑ de Gelder, Beatrice, and Mathieu Vandenbulcke. 2012. "Emotions as mind organs." Behavioral and Brain Sciences 35 (3): 147-148.

- ↑ Fodor, Jerry A. 1983. The Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ↑ Wolff, as discussed in Klein, 1970 [full reference to be provided]

- ↑ Lindquist, Kristen A. and Lisa Feldman Barrett. 2012. "A functional architecture of the human brain: Insights from Emotion." Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16: 533-540.

- ↑ Zola-Morgan, Stuart. 1995. "Localization of brain function: The legacy of Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828)." Annual Review of Neuroscience 18 (1): 359-383.

- ↑ Gall, quoted in Hollander, Bernard. 1920. In Search of the Soul. New York: E. P. Dutton.

- ↑ Marshall, John C. 1984, "Multiple perspectives on modularity." Cognition, 17: 209-242.

- ↑ Fodor, Jerry A. 1983. Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 22.

- ↑ Historical and modern approaches to the mental organ hypothesis do not necessarily agree on which mental organs exist, other than in gross generalities.

- ↑ Laland, Kevin N., and Gillian R. Brown. 2002. Sense and Nonsense: Evolutionary Perspectives on Human Behaviour. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ For an accessible discussion of this issue, read The Beak of the Finch by Jonathan Weiner.

- ↑ Pinker, Steven. 1997. How the Mind Works. New York: Norton.

- ↑ Cosmides, Leda, and John Tooby. 2000. “Evolutionary Psychology and the Emotions.” In Handbook of Emotions, 2nd edition, edited by Michael Lewis and Jeannette M. Haviland-Jones, 91–115. New York: Guilford Press.

- ↑ Buss, David M. 1994. The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating. New York: Basic Books.

- ↑ Pinker, Steven. 1994. The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. William Morrow and Company.

- ↑ Cosmides, Leda, and John Tooby. 2000. “Evolutionary Psychology and the Emotions.” In Handbook of Emotions, 2nd edition, edited by Michael Lewis and Jeannette M. Haviland-Jones, 91–115. New York: Guilford Press., p. 93.

- ↑ Silvan Tomkins’ early concept of “affect programs” is similar, but more metaphorical; emotion programs are thought to be localizable in the brain, literally.

- ↑ Pinker, Steven. 1997. How the Mind Works. New York: Norton, p. 30.